Posted July 19, 2018

By Jason Young

This project was largely inspired by a 2014 collaboration between UNESCO and Worldreader, which sought to develop “insights into how mobile technology can be leveraged to better facilitate reading in countries where literacy rates are low.” (UNESCO 2014, 9) The problem of increasing literacy is particularly tricky in many of these contexts, since educational opportunities – including those offered through mobile devices – are often not equally accessible by all segments of the population. In fact, some of the most interesting findings of the UNESCO (2014) report describe how gender mediates not only access to the Worldreader application, but also how the app is used once individuals do gain access. On the one hand, the report found that male users vastly outnumber female users, by a global 3:1 ratio. In some countries, including Ethiopia and India, that ratio was as high as 9:1. On the other hand, though, those women that did access the Worldreader app tended to use it more than did the men. For example, women made up the bulk of the most active users of the application, accounting for 66% of total reading time on the app.1

These results are important, because they directly engage with the relationships between information and communication technologies (ICTs), educational opportunity, and gender inequality. Worldwide, and especially in regions of the Global South such as sub-Saharan Africa, there is a gender gap in access to education that results in fewer opportunities for women. For example, a UNESCO (2015) study found that a large gap exists between global literacy rates for men and women, both for youth (92.2% of men are literate, 86.8% of women) and adults (88.6% of men, 79.9% of women). If women tend to have very high engagement with mobile reading applications, and if that engagement translates into increased female literacy, then it is possible that mobile apps can help to overcome these broader gender inequalities in education. However, if women have lower access to the apps, then those apps may contribute to educational gaps since it is primarily men receiving the benefit. These dynamics around mobile phones and gender equality are increasingly studied under the banner of digital gender divides, with similarly mixed results (e.g., Alozie and Akpan-Obong 2017; Nguyen and Ramaswami 2017; Reychav et al. 2017; Wyche and Olson 2018). These studies generally find that women have less access to mobile phones, and also tend to use their phones for advanced (and costly) features, such as mobile internet, less often than men (GSMA 2015; UNESCO 2015). Women face barriers to access including high costs and lack of employment, gender-based harassment, repressive social norms, lower technical literacy and access to technical education, lack of free time, lack of relevant content and gender-sensitive design of apps, and more (Alozie and Akpan-Obong 2017; GSMA 2015; UNESCO 2015). However, UNESCO (2015) found that “women turn out to be more active users of digital tools than men” (26) when controlling for variables such as employment, education level, and income. Furthermore, it seems that women do tend to recognize the value of increased access to mobile devices (GSMA 2015). These findings reaffirm the notion that mobile phones and applications can be important tools in overcoming gender inequality, but only insofar as barriers to access are lowered.

Based on this context, we have been interested in extending the gender-based analysis of UNESCO’s (2014) earlier report to Worldreader’s current database. Primary questions for us included:

To answer these questions we explored the log data of registered Worldreader users from June 2016 through March 2018.2 It is important to highlight some of the differences between this dataset and the data used in the UNESCO report, in order to understand the constraints of this analysis. For the UNESCO (2014) report, the analysts had access to a prior iteration of log data, a survey delivered through the Worldreader app, and qualitative telephone interviews. The survey data was particularly useful for this study, since it allowed the researchers to collect data on gender in a systematic way and alongside other demographic information. This could then be triangulated with the log data to enable richer and more generalizable analysis. In contrast, we are only able to glean gender data from the log database. Only registered users are able to indicate their gender within the app, and only about half of registered users actually attach demographic data to their profile. This means that, of 58,455,021 rows attached to unique user or client IDs, we are only able to perform analysis on 462,121 rows, or 0.79% of the rows. This isn’t inherently a problem, given that it is still a very large sample size. The problem, as we’ve discussed in previous posts, is the sampling method – or lack thereof – used to select those users that provided their gender.

We are working with a convenience sample, since our sample is defined by those users that chose to (1) use Worldreader, (2) optionally register with Worldreader, and (3) optionally fill in their gender on the registration page. Like many other big data sets (e.g., Giardullo 2015; Kaplan et al. 2014; Lugmayr et al. 2016; Price and Ball 2014; Seely-Gant and Frehill 2015; Tufekci 2014), this approach to data collection leaves open the very large possibility of selection bias. Sampling bias is a systematic error in the data created by the method in which individuals were selected for inclusion, which led to some types of individuals being over- and underrepresented in comparison to the characteristics of the broader population. In this case, the concern is that the characteristics of the people that choose to record their gender in the app are different from the characteristics of broader populations such as all Worldreader users, all mobile reading application users, or all individuals in the Global South. There are various, plausible scenarios that might produce selection bias:

Given these possibilities for selection bias, it becomes quite difficult for us to generalize any findings from this analysis to other populations. It is therefore not particularly useful to leverage more advanced statistical techniques focused on generalizability, especially given that reading behavior within our sample is not normally distributed and that users might not be truthful when recording their gender [Footnote: This is even more problematic given that users are only presented with a binary gender choice, which doesn’t leave a correct option for individuals with a non-binary gender identity. Of course, it would be difficult for Worldreader to present users with non-binary options, given the political issues surrounding sexual orientation across many of the geographies they serve. This adds another dimension to our earlier discussion of how ethics and politics impact this project (insert link to ethics post).]. We are therefore restricted to an examination of the descriptive statistics of the sample itself, with some qualitative interpretation of those statistics. This allows us to understand some limited things about the sample population itself, but not about broader populations of Worldreader users or mobile readers. Nevertheless, the findings are interesting and help point us toward gender-based questions that we should ask about the broader Worldreader population with future (and more statistically rigorous) studies.

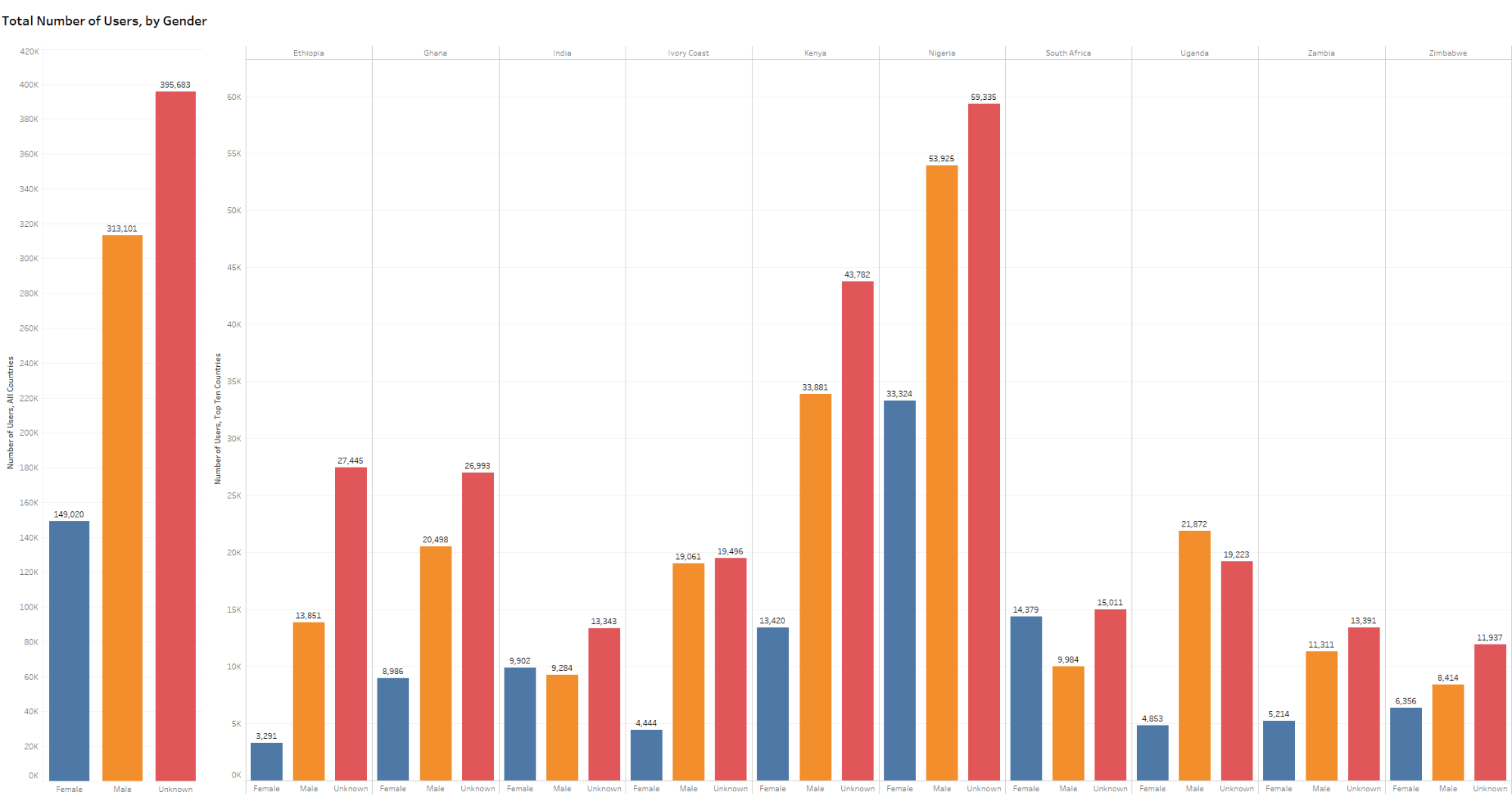

Given those qualifications, the results of this analysis are quite consistent with the earlier analysis within the UNESCO (2014) report. First, men continue to make up a majority of the users registered within the application, although this gender gap is narrower than that reported by UNESCO. Of the users that recorded a gender, 149,020 (32%) indicated they were female and 313,101 (68%) indicated that they were male. This gender gap does not change much if you filter out users that have not read any pages – this results in 96,024 (34%) female users and 188,123 (66%) male users. At the time of the writing of the UNESCO report, only 23% of the analyzed users were female. As Figure 1 shows, this gender gap is relatively consistent across the countries with the top ten count of Worldreader users. The most notable exceptions are India and South Africa, where there are more female users than male users. In the eight other countries there are considerably more male users, ranging from 32% more in Zimbabwe to over 400% more in Uganda and the Cote d’Ivoire.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

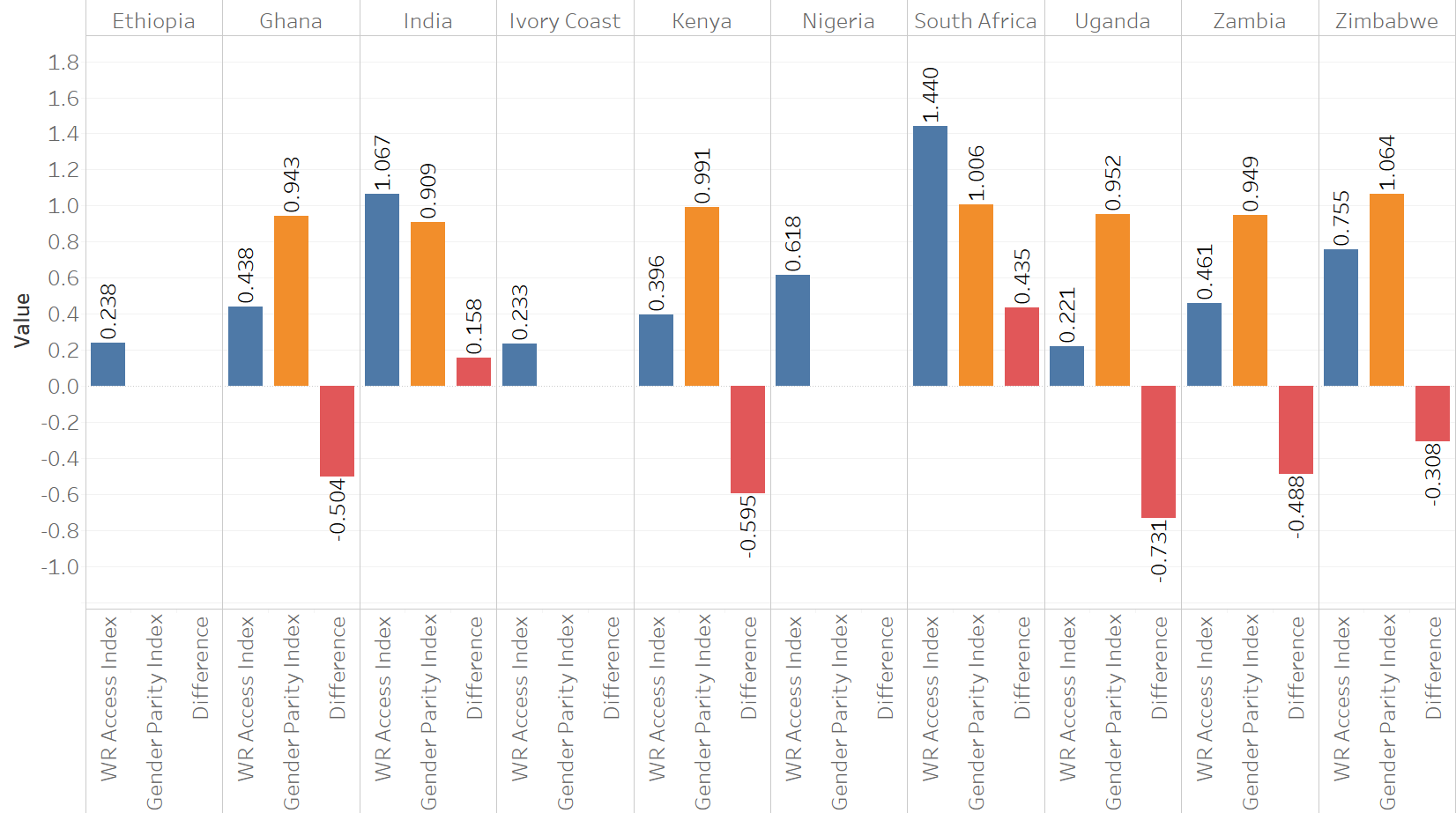

Given that we are interested in whether reading applications offer women a leg-up in education, it is also worthwhile to compare their access to the Worldreader application to their access to more traditional forms of education. Even more than the raw counts discussed above, this comparison can offer some insights into whether digital technologies are a good option for overcoming gender-based inequality in education. We therefore chose to compare gender inequality within the Worldreader data to UNESCO’s 2016 Gender Parity Index. The Gender Parity Index is calculated by dividing the literacy rate of women in a country by the literacy rate of men. A value of 1 means that men and women are equally literate, a value of less than 1 favors men, and a value over 1 favors women. To facilitate comparison, we performed a similar calculation with our data by dividing the number of female users in a country by the number of male users. While this isn’t a perfect comparison, it does provide similarly indexed values to understand how levels of access to Worldreader compare to levels of access to support for developing literacy. Figure 2 depicts the Gender Parity Index, the index calculated for Worldreader, and the difference between the two indices. Unfortunately, it does not provide a more optimistic picture than the analysis above. Except for India and South Africa, access to the Worldreader app has a larger gender gap than does the literacy rate of the country. This is not a promising result if one’s motivation is to use mobile applications to reverse broader educational inequalities. However, it does raise questions as to why women have such high levels of access to the Worldreader application in India and South Africa. Is this a result of other population characteristics in these two countries (such as wealth), increased accessibility of technology and infrastructure, availability of popular content in these countries, Worldreader programs, or something else? Answers to these questions may help point to solutions for overcoming gender inequality in access to mobile reading applications.

Figure 2. Data from UNESCO;s 2016 Gender Parity Index and Worldreader's Log Data

Figure 2. Data from UNESCO;s 2016 Gender Parity Index and Worldreader's Log Data

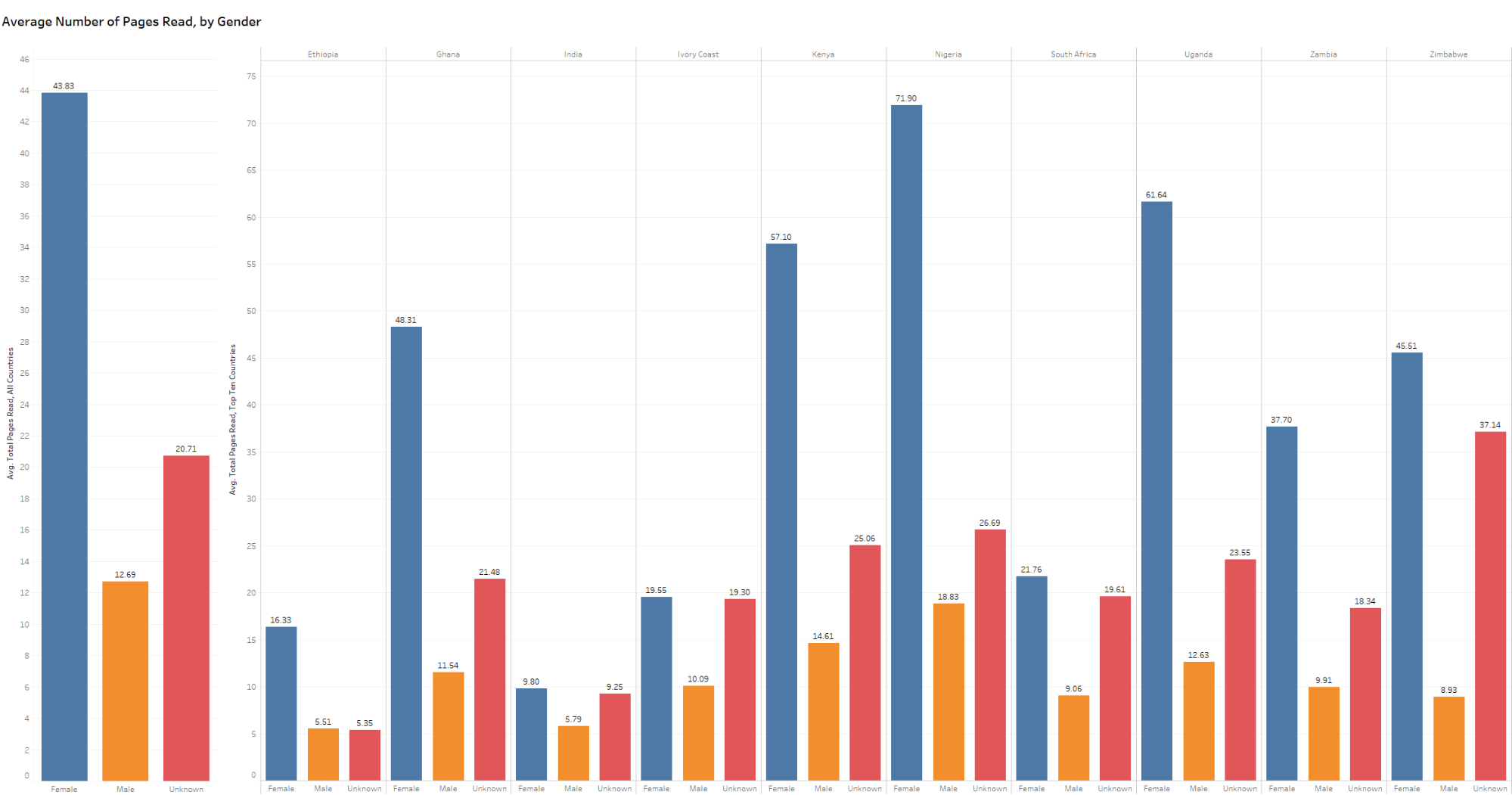

In contrast to these inequalities in access, our analysis also supports UNESCO’s (2014) previous findings that female users are generally more active than male users. We looked at averages, both globally and in the top ten countries, of measures including log events per user, number of books accessed, amount of time between first and last recorded log event, and number of pages read (as indicated by the book_page variable).3 For each of these we looked at both mean and median values by gender. Values for female users were almost universally higher than male users, except for a few instances where median values were equal between female and male users in some countries [Footnote: this occurred for median number of books accessed and median number of pages read.]. Figure 3, for example, shows the mean number of pages read by gender. Globally, female users averaged about 44 pages while male users averaged approximately 13 pages. This gap is quite consistent across all of the top ten countries. These averages are tilted toward female users the most in Zimbabwe and Uganda, which is interesting given that these two countries fall on opposite sides of the spectrum of gender equality in terms of access to the app.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

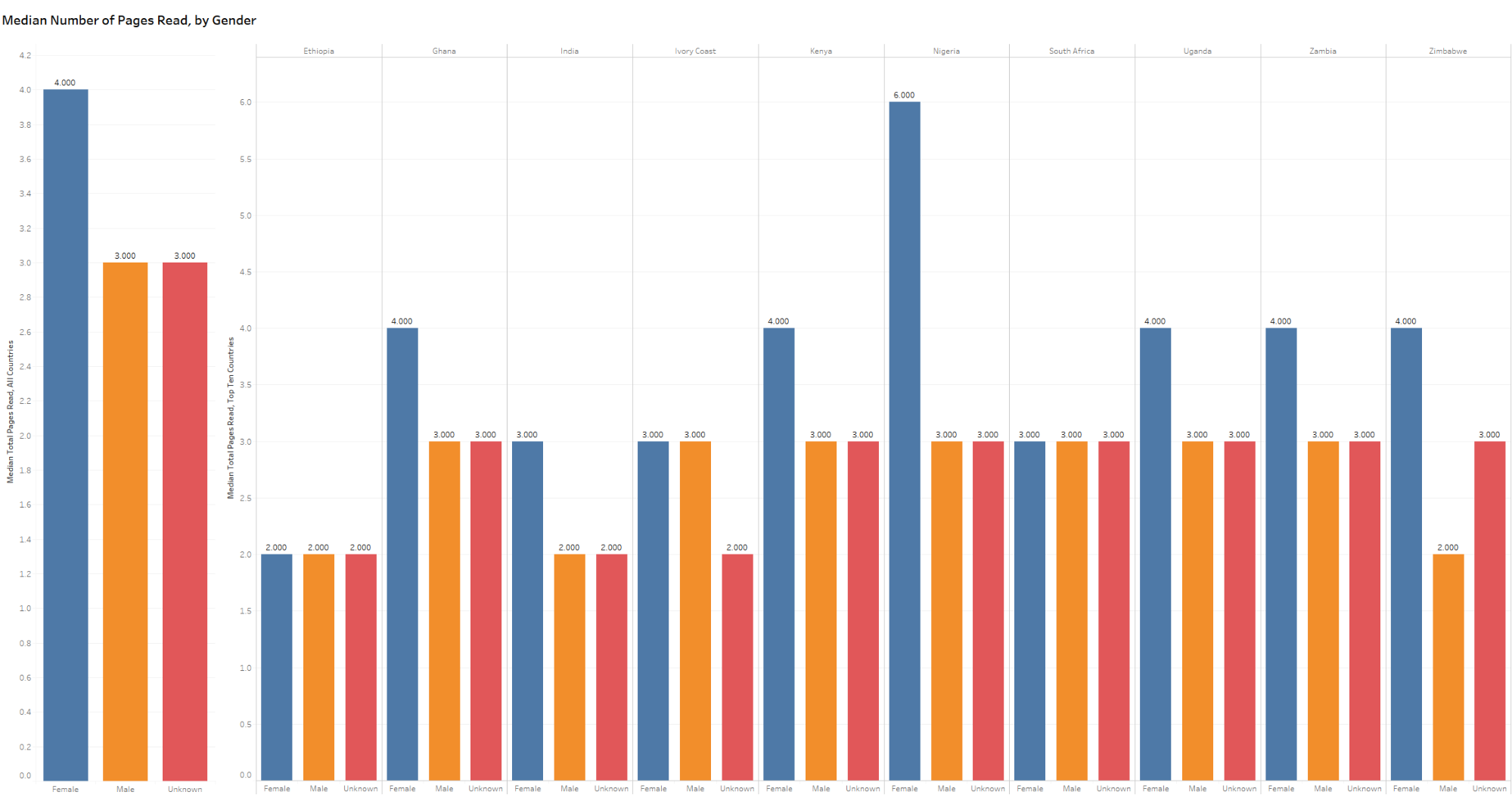

These gaps are considerably smaller when one looks at median values, but female users still tend to come out ahead or equal. Figure 4 shows median number of pages read by gender. Perhaps what is most striking about this figure is how very low the median values are across the different geographies, with only women in Nigeria (barely) breaking a median value of 5 pages read. This reflects the fact that a large number of Worldreader users are not retained past a few pages of reading, and that a few very active readers are pulling the mean values up in many cases.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

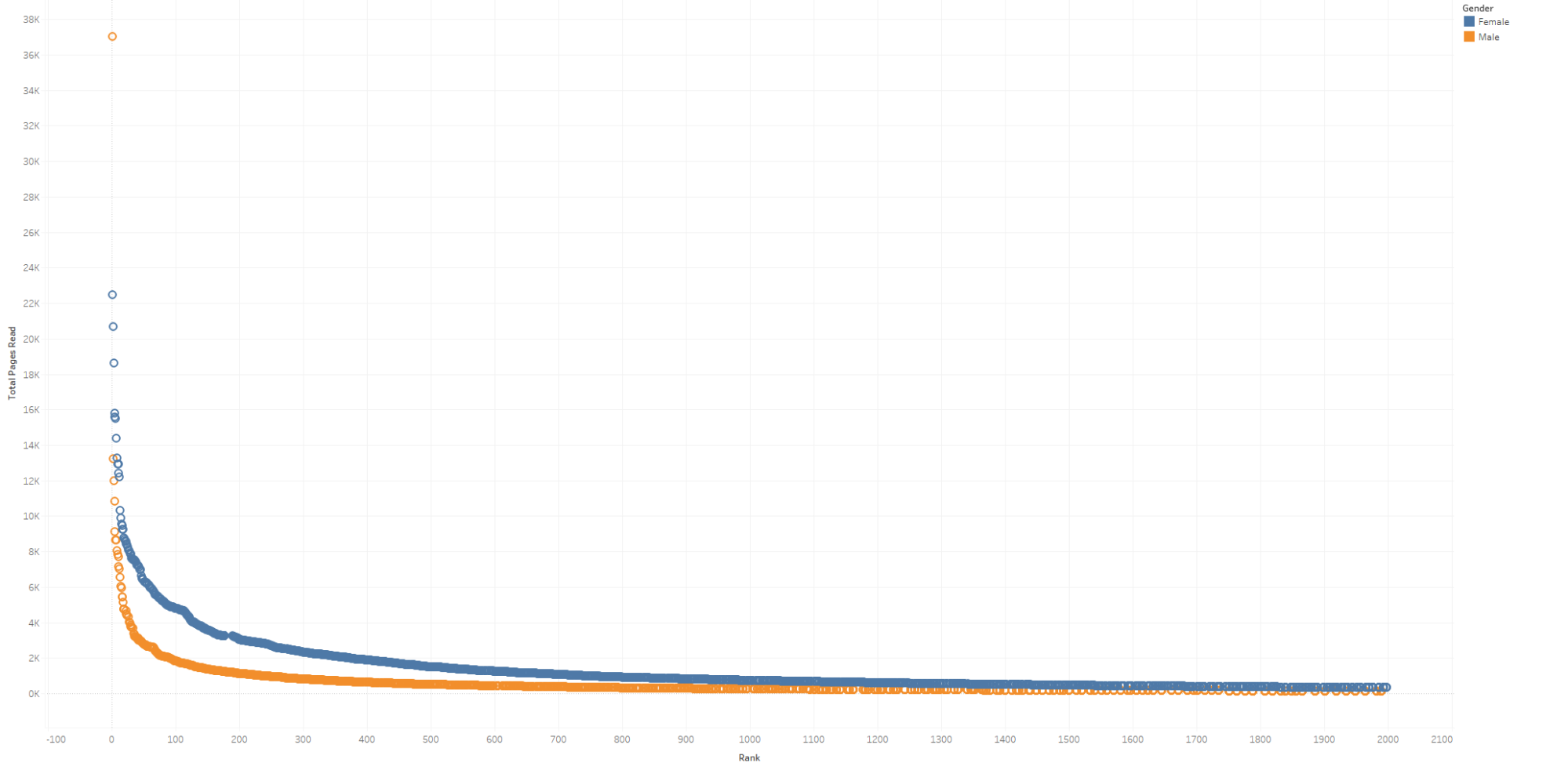

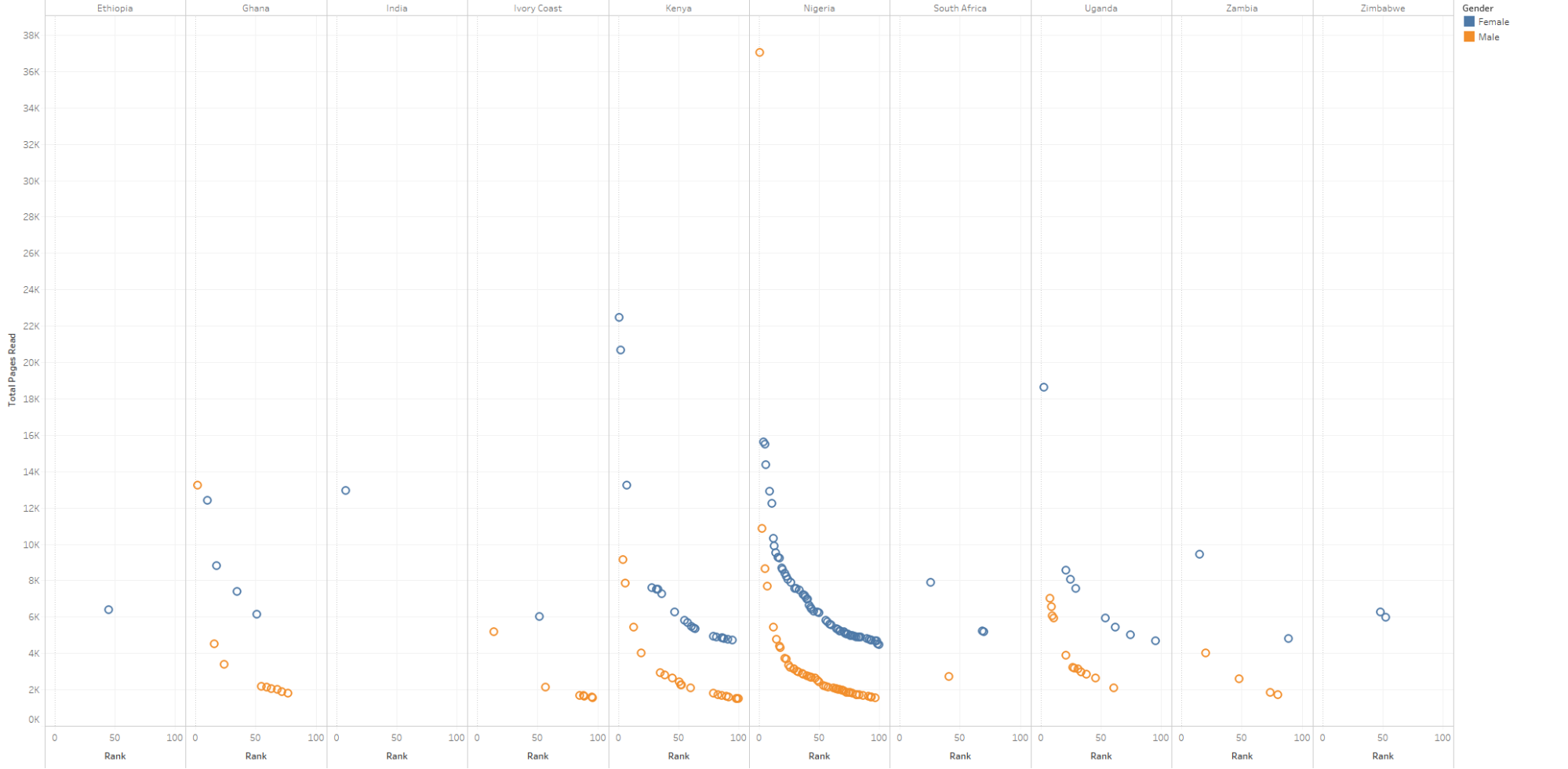

These very active users are also dominated by women, with gains over even the high values reflected in the UNESCO report. The UNESCO report found that female users made up 59% of the top 2000 Worldreader users, 72% of the top 1000 users, and 80% of the top 100 users. In this case a top user was calculated based on time spent reading in the app. During the course of this project we were not able to calculate reading times for individual users, so we looked at top users as defined by the number of pages read. When examining only registered users that provided a gender, female users make up 73% of the top 2000 users, 75% of the top 1000 users, and 82% of the top 100 users. Figure 5 compares the number of pages read by the top 2000 female users with the number of pages read by the top 2000 male users, where the users are ranked by the number of pages they have read. It shows a considerable gap between the two sets of users. This gap extends to individual countries as shown by Figure 6, which looks at the top 100 users across the top ten countries, binned by country.

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

These analyses raise interesting questions for further study. To what extent might these findings apply to broader populations, and therefore more general patterns of access and digital reading by gender? What barriers are driving the gender inequality in access that we see in this analysis? What factors are driving increased female activity within the application? Do any of these variables, such as number of pages read, act as a proxy for the quality of users’ engagement with the Worldreader application or for the app’s educational potential? Unfortunately, many of these questions cannot be answered without additional data collection. For example, it would be useful to collect additional demographic information about Worldreader users, so that we can control for variables such as wealth, employment, presence of children, education level, and more (see Alozie and Akpan-Obong 2017). It would be even more useful if this data could be collected in a systematic manner, such that resulting analysis could be more easily generalized. Second, as another recent UNESCO (2015) report on mobile phones and literacy points out, “quantitative methods are limited in reaching deeper into the socio-cultural interactions surrounding women’s acquisition and application of literacy skills in their immediate community contexts” (98). Qualitative surveys and interviews, and preferably those carried out longitudinally, would be very useful in adding further explanatory value to the quantitative analysis that can be done with Worldreader’s log data. These types of studies would not only help to describe the current digital gender divide as it applies to Worldreader’s services, but may also provide insights into how to shape interventions (e.g., GSMA 2015) that improve the ability of mobile reading applications to narrow the gender gap in global literacy.

Alozie, NO and P Akpan-Obong. 2017. The Digital Gender Divide: Confronting Obstacles to Women’s Development in Africa. Development Policy Review. 35(2): 137-60.

Giardullo, Paolo. 2015. Does ‘bigger’ mean ‘better’? Pitfalls and shortcuts associated with big data for social research. Qual Quant. 50: 529-47.

GSMA. 2015. Connected Women - Bridging the Data Gap: Mobile Access and Usage in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. GSMA.

Kaplan RM, DA Chambers, and RE Glasgow. 2014. Big data and large sample size: a cautionary note on the potential for bias. Clin Transl Sci. 7(4): 342-46.

Lugmayr, Artur, Bjoern Stockleben, and Christoph Scheib. 2016. A Comprehensive Survey in Big-Data Research and Its Implications – What is Really ‘New’ in Big Data? – It’s Cognitive Big Data! PACIS 2016 Proceedings. Association for Information Systems

Nguyen H and A Chib. 2017. Mobile Phones and Gender Empowerment: Negotiating the Essentialist-Aspirational Dialectic. Information Technologies & International Development. 13: 171-85

Price M and P Ball. 2014. Big Data, Selection Bias, and the Statistical Patterns of Mortality in Conflit. SAIS Review of International Affairs. 34(1): 9-20.

Reychav I, R McHaney, and DD Burke. 2017. The relationship between gender and mobile technology use in collaborative learning settings: An empirical investigation. 113: 61-74

Seely-Gant, Katie and Lisa M. Frehill. 2015. Exploring Bias and Error in Big Data Research. Journal of the Washington Academy of Science. 101(3): 29-37.

Tufekci, Zeynep. 2014. Big Questions for Social Media Big Data: Representativeness, Validity, and Other Methodological Pitfalls. ICWSM ’14: Proceedings of the 8th International AAAI: Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

UNESCO. 2014. Reading in the mobile era: A study of mobile reading in developing countries. Paris: United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO. 2015. Mobile Phones & Literacy: Empowerment in Women’s Hands. Paris: UNESCO.

Wyche S and J Olson. 2018. Kenyan women’s rural realities, mobile Internet access, and ‘Africa Rising’. Information Technologies & International Development. 14: 33-47.

Findings of the UNESCO report showed that while less women were reading on their mobile app, those women that were reading were consuming 6x more content per month than men. As a result, Worldreader began exploring this gender divide in 2016 through the Anasoma project in Kenya. The Anasoma Project aims to increase female participation in mobile reading and positively influence gender social norms and stereotypes, by identifying the barriers of and drivers to female mobile readership as well as by testing new empowering and engaging content through the Worldreader mobile app. For more information see the Anasoma Midterm Report. ↩

This is a longer time period than some of our previous analysis, given that it occurred later in the study. ↩

We originally understood the book_page variable to indicate the “page number of the book with which the user is interacting” (see Data Variables blog post). However we have since discovered that book_page was not, in fact, an accurate indicator of the reader’s progress through the content of a book. The book_page variable actually indicates book “chunks” - a variable associated with different character counts according to the book and delivery type in question. One book chunk is often indicative of many pages but this varies widely by book. ↩